Review: As We Forgive, Griffin Theatre Co

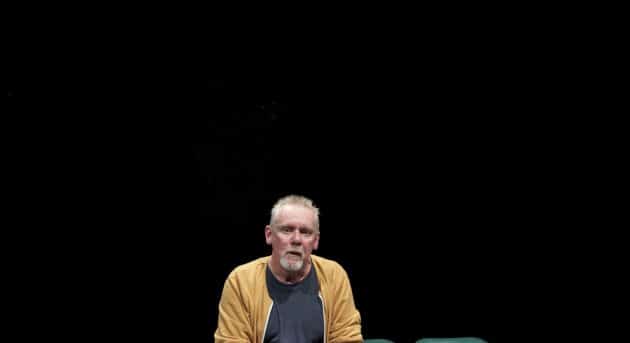

Robert Jarman stands alone on the SBW Stables stage proper. Against the wall, near the entrance, a cellist (Jack Ward) plays something sombre (by Raffaele Marcellino) . Blurred, aged projections (Lisa Garland) flicker above Jarman’s head, showing title cards, definitions of forgiveness, and more. This is As We Forgive.

Tom Holloway has written three monologues approaching the concept of forgiveness from different and morally challenging angles. There is a man who has crossed a line after suffering a loss of his safety; a man reeling from childhood abuse; a man trying to live with his crime.

Under Julian Meyrick’s direction the monologues are considered, naturalistic, and smartly never sensational. Anchored by Holloway’s gorgeous language – colloquialism writ lyrical – Jarman never seems like an unreal figure.

But it’s just not compelling. The monologues unfold in a bafflingly similar way: the man addresses the audience to explain his circumstances. In a play with such a short running time and little variation, this same-ness begins to feel stifling and even boring, despite Jarman’s remarkably nuanced performance.

And Jarman is remarkable. He creates three starkly different men onstage and they are all oddly likeable. He’s gentle, thoughtful, and shot through with steel: in the affecting first monologue he seems fragile, but it’s never at adds with his aversion to apologia.

In Meyrick’s program notes, he says: “who are the men in As We Forgive? … The answer is: anyone. They could be anyone.” But this play is not entirely universal. These men could perhaps be any man, but the arcs of each character and his relationship with aggression, violence, and – yes – entitlement – is staunchly male.

This isn’t a bad or negative thing, and it’s impressive that Jarman can in just over an hour present a thoughtful, subtle study of many different kinds of masculinity on stage. It’s just difficult to picture that, in a society that is structured to favour and excuse men their violence while punishing women for theirs – in a country where violent crime is called a ‘man’s game’ – these stories could be universal.

But Jarman’s performance is exceptional, and Holloway’s language is always surprising in its gentleness, insight, and honesty. And sitting in the theatre on opening night, as the fate of Australia’s small-to-medium arts sector (and Griffin Theatre Co itself) hung in the balance, it was so clear that Griffin is essential as a champion of Australian playwriting, and to be thankful for a chance to experience a work created in Tasmania in inner Sydney.