Review: Turandot — Opera Australia

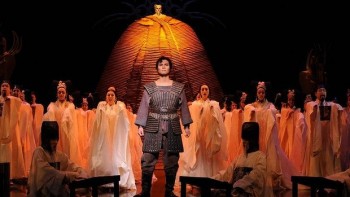

Graeme Murphy’s 1990 production of Turandot has an appealingly timeless quality; Murphy’s ensemble movement crests across the stage like waves, and Kristian Fredrikson’s design is dark and arresting and alive, enhanced by the lighting (by John Drummond Montgomery) that’s in turns warm and ice cold. It is a lavish, precise, indulgent staging and there’s a real sense of majesty of it.

Turandot is based on an old fable, the story of a terrifying princess (Turandot, Lise Lindstrom) who poses three riddles to her suitors. If they get them right, she must marry them (whether she wants to or not). But so far, no one has ever won the game, instead paying with their lives for the prvilege of playing. This changes when the Calaf (Yonghoon Lee), takes his turn, which he is compelled to do, of course, because he falls in love with her on sight. He gets the questions right. Turandot is dismayed and desperate. She’d rather the men be beheaded than being, essentially, bought by them. It’s difficult, these days, to be on Calaf’s side.

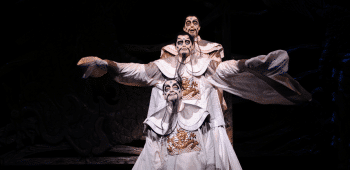

Seeing opera in 2015 can be difficult. There’s a fine line between high glamor spectacle and exoticism, and opera both treads and crosses the line frequently. Puccini’s commedia dell’arte take on Chinese advisers Ping, Pong, and Pang is just cringeworthy now, and while Murphy gives these characters the most ambitious choreography and staging, an intricate dance in giant scrolls, it doesn’t make their exaggerated makeup any easier to swallow. It’s also not a kind opera to women – Turandot loses all her independence because the Calaf loves her, or something, and her entire character is contradicted in the third act in her quick shift to love.

It’s very easy to start wondering why, as the same few dozen operas are staged over and over again, they generally aren’t interrogated, re-visited, with an eye to sensitivity. Opera Australia staged Bartlett Sher’s Lincoln Center production of South Pacific, a gently modernised, un-fetishised version of a problematic musical, so clearly the capacity for this kind of thinking exists at Opera Australia. It would be nice to see that carry over; to find ways into classic and gorgeous scores that affords dignity to the other.

Sometimes this makes it difficult to sort out the right critical approach to a production. With a sense of unease from a 2015 conscience — because we make art for now, not as a time capsule from 1926 — it can be hard to enjoy the good things, but there are good things.

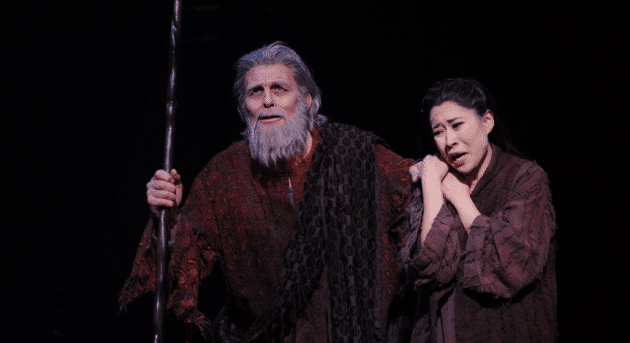

This production is sumptuous and you come close to drowning in the voices, but they’re too full of vigour and declaration to let anyone sink; they lift you up. The music is exciting, of course. Puccini died before he could finish the difficult, rewarding, exciting score — the ending was crafted by Franco Alfano. It’s perhaps not refined, but this production finds it own refinement in grace: in complex, gentle choreography; in Hyeseoung Kwon’s Liu, tender and strong; in Jud Arthur’s Timur, who seems to turn goodness into a physical quality. With Lindstrom’s clear and regal top notes, Yonghoon Lee’s dark oak bouquet, there’s something here to really sink into.

It’s remarkable that a production from 1990 still looks this good. But there’s worth in pushing the envelop, in engaging with these tricky issues of race and gender, viewing them through a lens to find the worth in these stories – to find the beating narrative and explore it in a way that doesn’t remind you that an opera was banned in the country it is set because of its offensive portrayal of the country, or of a way that lets a woman change her mind for a reason that’s not just a presumed magnetism – you can create agency in direction and design and subtle correction in technical tools and craft. You can make something we can proud of on a human level, bring opera out of a museum and into our current, living, breathing world. A little more of that, please.