Carrie – Squabbalogic review

Carrie’s life as a musical is notorious, legendary, intriguing. A resounding flop when it originally hit Broadway in 1988, it closed after only 16 previews and five performances. For the past several years, the creative team have been working on rehabilitating the classic Stephen King story, presenting a reworked and more cohesive version in a successful 2012 off-Broadway run. Finally, one of the best-known and least-seen shows in Broadway history comes to Australia, and it was well worth the wait.

To stage Carrie is a brave move. To stage Carrie is to believe in that magical, indescribable quality of musicals, and that space in which the story transcends words and finds itself in music; to celebrate the form’s sense of possibility, to take risks, to find beauty in the show’s strange and wonderful score, thematically desperate and pleading and wonderful.

To stage Carrie is to write a love letter to musical theatre.

What better way to end Squabbalogic’s 2013 season – a season that began with a loving wink and nudge spoof of Broadway, revue-style, and then brought us iconoclastic, barrier-busting emo-rock-musical-theatre about a contentious American President – than with a show that dares you to find its worth and tenderness and spectacle – and how it entwines the two – despite its reputation?

It’s another success for the small and dedicated company. They play this show straight: it’s sincere, never a joke. This production wants to tell the story of Stephen King’s novella and it does it well, and it does it sympathetically. It’s a well-known piece of horror history by now, with a movie remake hitting screens this month: mousy Carrie White, the school outcast with a deeply religious mother, has always been bullied and has never fit in. When things seem like they are about to turn around, and a boy even asks her to prom, the popular kids get their revenge on the girl who shouldn’t try to belong, and the results are bloody and catastrophic.

Squabbalogic understands that to make the show work, we must believe Carrie is a real and possible person. When bullied Carrie is in pain, we feel it; when her mother Margaret, tormented by ghosts of her past and God and his wrath, is tearing her heart to shreds, we hear it in the music and see it on stage. When Sue Snell tries to help ‘scary’ Carrie White, only to unwittingly set the wheels of carnage in motion, we feel for her.

The show is still not perfect; some of the lyrics seem a little hard to swallow, but the direction here pads them out in a wonderful self-conscious teenage pseudo-irony which is easier to believe. After a time, it’s best to stop focusing on the detail and focus on the characters instead; their story is more interesting than the narrative structure that surrounds it, which is the show’s only real and inexcusable flaw. However, in this production, it’s hard to stop and worry about flaws, because you’re watching something completely riveting.

This is perhaps the greatest feat director Jay James-Moody has ever pulled off: he makes Carrie: the Musical a moving, moody, blood-red meditation on teenage hierarchy and coming-of-age, of the demonisation and exploration of sexuality in small town life.

Adele Parkinson’s Sue Snell is the audience surrogate in the show; she is our eye into the before and after of the prom incident. She balances nimbly the competing interests of being a popular girl, but one with a soul, and Parkinson’s best gift as an actress in this role is her innate empathy; Parkinson feels every tragic misstep that powers the show along, brings it into her eyes, and it’s a pleasure to watch.

Rob Johnson is her boyfriend, Nice Guy Tommy Ross, who turns his nerves and relative inexperience in a featured role into an endearingly vulnerable young man; it’s not a show where you expect to really feel for the football player turned aspiring writer, but his awkwardness is charming, and so is his compassion for Carrie.

It’s a strong ensemble cast, particularly Prudence Holloway and Toby Francis as Chris and Billy, the mean girl and loser boy behind the pig’s blood, and there is an especially bright light in Bridget Keating’s Miss Gardner; her protective, hopeful number “Unsuspecting Hearts”, to encourage Carrie out of her shell, is genuinely touching. Keating has demonstrated broad comic chops in her prior roles (she was particularly sharp in Squabbalogic’s last outing, Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson), but here her malleable voice takes a sincere twang, with a Connie Britton style realism, an air of tough-but-fair.

The show, however, has found its beating heart not just in Carrie, but in Carrie and her mother Margaret together; every moment they are on stage and battling each other and failing to listen to each other and trying to understand each other is sad, thrilling, beautiful, elegantly macabre. Margi de Ferranti (Margaret) and Hilary Cole (Carrie) clutch at each other, comfort each other, hurt each other; they love each other so much they are unable to avoid destroying each other. It is heartbreaking.

Margi De Ferranti is in fine voice, wide-eyed and commanding, yet always a little far away; she is haunted all the time. Carrie, too, never escapes her mother’s ghosts, and her terror and its transformation into Carrie’s explosive anger and telekinesis is impressive.

Cole is a find and is revelatory. Fragile, birdlike, and aching to be invisible, it’s impossible not to instantly fall in love with poor Carrie. Cole’s vocal tone is so pure that it encapsulates all of Carrie’s hurt, hope, and fear and makes it somehow angelic; Carrie is otherworldly and the magnitude of her pain, and the blazing anger after years of bullying, is diamond-bright. Cole is mesmerising.

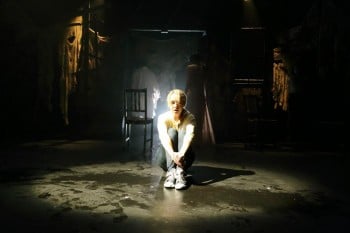

Snug in the Reginald theatre, the stage (designed by Sean Minahan) is a burnt-out gym, a grim reminder from the very start of the show’s end. It is eerie and foreboding, striking and effective. The smell of smoke and burning hangs acrid in the air – a nice touch.

James-Moody understands that Carrie isn’t a simple horror story – it’s a tragedy. When Hilary Cole sings her first number, “Carrie”, or when Margi de Ferranti sings “I Remember How Those Boys Could Dance”, they transcend caricature and become deeply human, and their struggle to be more than doomed is almost Shakespearean in its futility. When Adele Parkinson stands trembling in a spotlight, full of sorrow and regret, and when the ensemble dance together at Chris’s party, youthful and impulsive and somehow very real in such a hyper-real setting and show, this couldn’t be anything else but a sad, electric story.

On opening night, we left the theatre and walked into a thunderstorm. Lightning flashed, thunder roared; the message was clear: Carrie is here, and she will have your respect.