Review: Kinski and I, Sydney Fringe Festival

German actor Klaus Kinski (1926-1991) was an emotionally unstable, self-proclaimed sex addict. His autobiography recounted, in gleeful detail, his appallingly destructive obsessions. Two lawsuits led to its pulping. Kinski simply published another one.

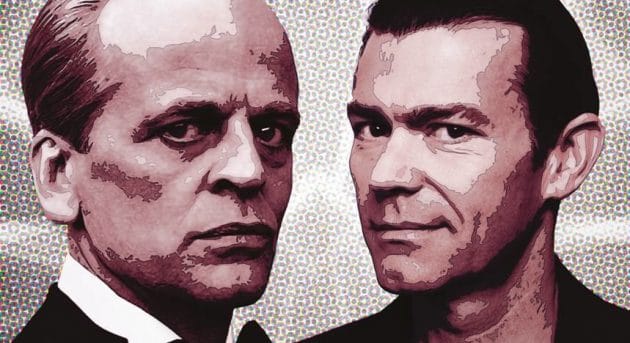

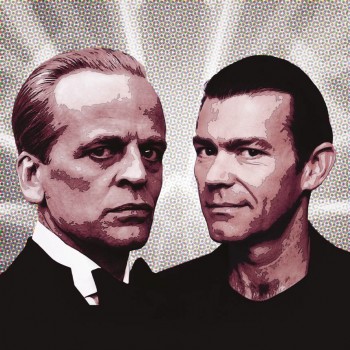

But at least one copy of the original survived and fell into the hands of ABC film reviewer CJ Johnson, who based his show on excerpts drawn from its pages.

For most of the presentation, Johnson stands at a lectern and reads. Using a German accent, he delivers Kinski’s words to the audience, beginning with a violent tirade of curses at director Werner Herzog during production of the 1972 film Aguirre, the Wrath of God.

Then Johnson steps forward, the house-lights come up, and he speaks to us as CJ Johnson rather than as Klaus Kinski. We learn, for instance, that he first saw Kinski in Aguirre at a screening at the Sydney Valhalla Cinema, and that he believes Kinski is one of the greatest screen actors of all time.

Certainly Kinski burns intensely on the screen, and evidence suggests the line between self and character was dangerously blurred. While still a young actor, he apparently locked himself in a bathroom for 48 hours, going over and over an up-coming role. Somehow, the basin and toilet bowl ended up ground to fine dust.

Why was he like this? The show suggests he was shaped by his childhood in Depression-era Berlin. His autobiography tells of bedbugs spraying blood onto the walls when squashed, but another disturbing story hints at issues beyond merely difficult circumstances: after talking of his mother’s shame at her rotten teeth, he describes her long lingering kiss on his mouth, and her arousing smell.

The 75-minute-long show condenses Kinski’s accounts of innumerable sexual partners, repeated doses of clap, three children, and foul-mouthed rage at—well, at everyone.

Kinski’s words, as delivered by Johnson, reveal a repellent but fascinating character. But the pared-down production style does not convey the gigantic dimensions of Kinski’s presence: his towering talent and frightening ego, anger, hungers, pain. Unfortunately, we are told about the psychopath, rather than shown. There is no story arc, no emotional trajectory, no character movement from one state to another.

And while there is a soundscape by David Stalley and videos cape by Laura Turner, the potential for a truly theatrical—and tragic—experience is not developed.

There is, however, one element that takes this show beyond a mere sexual freakshow. Kinski’s recitation of his adventures are, from time to time, interrupted by jarring words from his eldest daughter Pola, who in 2013, claimed her father sexually assaulted her for 14 years, beginning when she was 5 years old.

Pola’s words are spoken by Madeline Baghurst, who sits throughout the show at a desk on the side of the stage. Perhaps her Apple is a control panel; nevertheless, her acting role is another essentially static element in a story full of unfulfilled expressive potential.

Creative genius or monster? Kinski and I courageously allows this complicated and deeply uncomfortable question to remain unanswered, but giving Pola a voice—even a small one—shatters Kinski’s self-regarding, self-justifying monologue.