Review: A Steady Rain – Old Fitz Theatre

A Steady Rain is a gritty show in that you feel the dirt caught in your teeth as you watch it unfold; it’s not exactly a pleasant experience, but it grabs, and holds, your attention.

Keith Huff’s play, about dirty cops who are inevitably barrelling towards their own destruction (and the destruction of so many others), is absorbing without relief; the lighter moments are still coloured with muck.

Joey (Nick Barkla) and Denny (Justin Stewart Cotta) are not nice guys, even though Joey has a whiff of Nice Guy Syndrome about him. They are on the take, or turning a blind eye to someone who is; they are alcoholics, probably lightly traumatised by their jobs as cops on the local seedy beat; they are casual racists with an axe to grind, convinced they’re not making detective because their spots are being filled by an imaginary equal-opportunity program favouring minorities (because it couldn’t possibly be that they’re arrogant, entitled, and unthinkingly cruel).

The one redeeming thing about Joey and Denny is their partnership – at least at first. They’re like brothers, they say. Best friends since kindergarten. Saving each other’s lives from the bottle, from loneliness, from Denny’s terrifying temper. It’s almost enough to make you like them.

But maleness, especially in popular-culture and entertainment, is all about letting the anti-hero, the unlikeable protagonist, have a moment, so we’re used to this: we don’t have to like these cops. We just have to listen to the story.

Huff’s script is not especially well written, particularly when it attempts to draw genuine sympathy from the audience (the kinder hearts will find pity enough towards the end without it) but it’s crime-novel tense (it’s every crime novel) and more than a little effective. It’s direct and knows how to build tension until it’s unbearable.

Someone throws a brick through Denny’s window. Glass shatters everywhere, all over his wife and young family. His baby son is injured; the boy’s life hangs in the balance. As Denny becomes consumed by revenge and by the oblivion that comes from acting without thinking, Joey moves into the role of protector, and the more Denny departs his life to seek justice, the more Joey takes his place.

This is a wearying premise and it’s especially wearying in the Old Fitz in 2015, which continues to concern itself largely with damaged men and their struggles; A Steady Rain is well directed, staged and produced but its impact is greatly lessened by the shows that came before it. These are stories that shove women to the side and dispose of them to explore how it makes a man feel (like history and society in general) and it’s beginning to become alienating, particularly considering the ratio of men to women as directors and creative in the season (women are the clear losers here). This will hopefully be addressed in Red Line’s second year of operation at the theatre, because it’s easier to forgive a first season its bias than its second.

But A Steady Rain is a good, solid production of a fairly average play that doesn’t pretend to be anything it isn’t.

This isn’t a play to enjoy and it wasn’t a play I liked (these kinds of broken men are glorified far too much in art and culture for my liking, and women and minorities are constantly used, discarded, and killed to further the mens’ own emotional journeys so casually it’s sickening, a reminder of perceived lesser importance of these groups by good old white men) but the production, helmed by Adam Cook, is a good one. The technical elements are all harmoniously, nail-bitingly alive; lighting by Ross Graham amplifies the shadowy desperation Denny steers into once that brick hits his window, and sound design by Jed Silver is almost disturbingly visual – the rain, the streetlife.

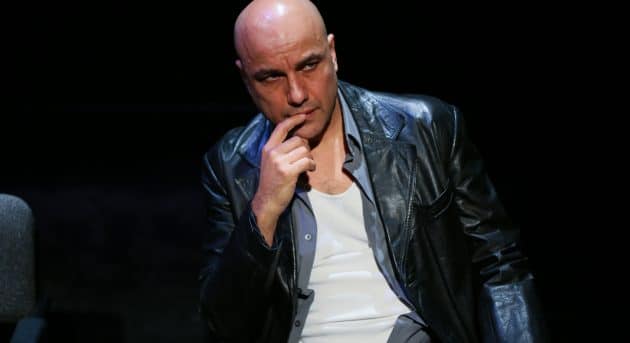

Cotta, as an actor, is incredibly good at simmering: that process of building his rage and pain to a boil before it unstoppably consumes him, and the play at large. His Denny is mean and protective and complex; he is the wreck you can’t stop watching. Barkla, as his more mellow counterpart, embraces the pathetic, the sidekick, the damaged. His performance is smaller, because it must be, and it all sits in his face: in his brows, his eyes, the way his mouth twists. He and Cotta work extremely well together.

The best value in Cook’s A Steady Rain is an example of how crucial these technical elements are, and how crucial game performances are, to a play; they elevate the material exponentially.

I would not say that women in this play are minor, used etc. Denny’s wife is a hidden character, but she is someone anchoring those two together. Also, Joey is not just a weak damaged person. He has very define set of targets, with or without thinking of them, actually. He is more gentle, not a cruel as Denny, at the end.

Yes, males world. But there is 50% of males around, and problems of that world are not less important then ours. Frankly, I even do not believe into that division – males, females. Women shall watch these things to understand men better. Even in that “dirty” appearances. More knowledge – better connection is possible, isn’t it?

For me, both of those two are complex enough to be mono-colored.

Also, it is strange to me that entire review is placing those cops of a dirty dark side of life, opposite to “normal”; in contrast to something what is ok “to like”.

Who says those people are rear and not around us every day? There is no warranty that each of us will not make the decision like those two made about that Vietnamese boy. Unless there is a warranty from a god, or something.

Where are they racists? If that boy would be a white child, they would be called … how? That episode, for me, is not about being racist, it is just about being not involve, cold, ignorant, heartless.

Yes, play is not the most impressive one. But the power put in there by Nick Barkla and Justin Stewart Cotta

scores a big respect. That power for me means that they read in some serious message in this play, and i think it i fair to guess what it is.