The Last Confession

His Majesty’s Theatre is a fitting venue for David Suchet’s touring vehicle The Last Confession: it’s a bit old-fashioned, and the red interior goes well with the costumes and set. Even the smell of incense wafting through the auditorium didn’t seem out of place as we walked in, and there is a slight hallowed quality about the theatre that is not too dissimilar to what you’d find in a grand old church. So with that kind of pre-ordained semi-ecclesiastical ambience, The Last Confession should have hit the spot.

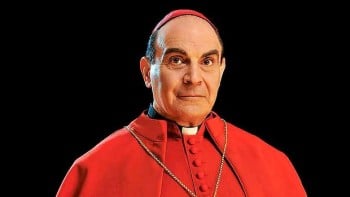

Mr. Suchet should have stolen the show as the dying Cardinal Benelli, but the script just didn’t provide a meaty-enough character for him to sink his teeth into. In fact, his character’s crisis of faith in the face of death and judgement was far less compelling than the gentle fierceness of Cardinal Luciani’s (Richard O’Callaghan) rise to power and short reign; O’Callaghan’s reluctant Pope John Paul I conveyed a sweetness that belied a lion’s courage. Make no mistake, Suchet is compelling to watch; he is extremely precise and never misses a beat. In fact none of the cast miss a step; the action moves forward like clockwork, and the Catholic dogma-heavy dialogue rolls out like a well-oiled machine.

The conspiracy theory at the centre of the piece is interesting and could have been sensationalised in Shakespearean fashion to amp up the drama in this historical drama; instead it’s dry and fairly un-thrilling for a so-called thriller. The stakes aren’t very high for these privileged high-ranking officials, who either get to stay in Rome and live off the fat of the Catholic bank and write edicts, or risk being relocated to some other cushy-yet-slightly-less-glamorous parish. However, the script does do an excellent job of reinforcing just how detached, irrelevant and hypocritical some of the Church’s views were at the time of this implied coup.

The whodunit factor is mostly non-existent, so if one was expecting a murder mystery neatly wrapped up with a cardinal red ribbon up at the end, they could come away dissatisfied. This piece is probably best suited to an audience with a vested interest in historical drama, or for those with more traditional tastes when it comes to theatre. The set, designed by William Dudley, was really the only thing non-traditional about the show, but the constant reconfiguring of the trucks between scenes was distracting and unnecessary. Turning these trucks 90 degrees to the left to tell us we’re in a new location is an inefficient use of time and space; really all we need is the script and the actors to tell us where we are.

The characters joke about how bad the coffee at the Vatican is. Of all places, smack dab in the middle of espresso country, with all the Church’s gold and tithes, the Pope can’t get a good cup of joe until his Girl Friday, Sister Vincenza (Sheila Ferris), gets rid of the old coffee maker.

Which brings me to my point: all the Pope’s horses and all the Pope’s men couldn’t make this drama percolate.