This is not a one man show – it involves us all: Tim Crouch talks all things I Malvolio

I, Malvolio, hate you.

Look at you. Sitting there with your bellies full of pop and pickled herring. Laughing at me. Go on. Laugh at the funny man. Laugh. Make the funny man cry…

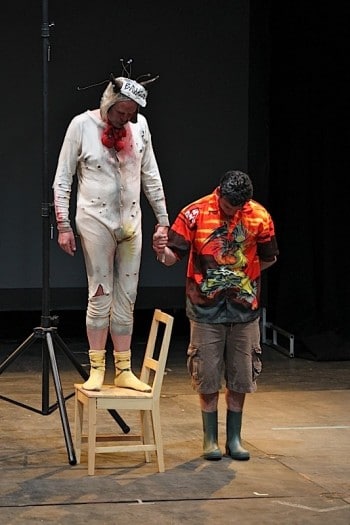

Part Monty Python and part Black Adder, I, Malvolio is the fourth in a series of plays by Tim Crouch which takes minor characters from Shakespeare’s works and gives them the opportunity to have their say, in this case, Malvolio from Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night.

The show is both written and performed by Tim who is known internationally as a clown, an expert in Shakespeare, and one of England’s most innovative and popular playwrights. The show has left audiences shaking with laughter all over the world, and for one week, Melbourne will get its opportunity to join the fun.

I, Malvolio will be playing the Arts Centre from 6 January 2015. Bookings can be made via Arts Centre Melbourne’s website for as little as $30.

In the meantime, thanks to our wonderful friends at Arts Centre Melbourne, Chris Fung spoke with Tim to ask a bunch of impertinent questions.

Have you ever worried: “Who the hell am I to re-write and adapt bits of Shakespeare? What kind of jumped up ponce do I think I am”?

What kind of a jumped-up ponce was Shakespeare to re-write and adapts bits of Plutarch, Boccaccio, Holinshed, Ovid, Plautus, etc?

I don’t worry about this. I think it’s what he would have wanted. Anything that keeps Shakespeare’s stories and characters alive for a contemporary audience is okay by me. Also, he’s been dead a long time.

All art deals with the given. Shakespeare, in theatre and in culture, in how we think about ourselves, is a given and he must be dealt with – not with hagiographic respect but robustly and contemporaneously. Next year I’m working with a physical clown company called Spymonkey on a piece we’ve called The Complete Deaths – every onstage death in Shakespeare performed in 90 minutes. It’s to honour the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death in 1616. Ponce that.

What do you find so appealing about playing Arts Festivals and different theatres around the globe?

In 2014, Malvolio played in China, Poland, Brazil, Malta, Switzerland, the UK and Australia. I try to make work that is open to its audience – and this makes international touring particularly interesting. I engage fully with the culture of my audience – and with a country’s audience culture in general. China was fascinating because there is a great respect for the performer (the ‘master’) in their culture. I believe that respect should be earned in the moment. I had to work hard in China to reduce that presupposed esteem! The performances become a dialogue between the audience and the stage. This is why I like travelling so much. I meet so many different people – whilst performing.

In “I, Malvolio” you use direct audience address a great deal, what is the closest you have come to being wrong-footed by an unexpected response?

I’m always surprised at solo shows that don’t address the audience. I, Malvolio is only ever direct address – the audience are the other people in the room and it would be rude of me not to talk to them.

I have written I, Malvolio in the hope that I will be constantly wrong-footed by the audience. I want the audience to misbehave, to arrive late, to keep their phones on, to scorn and trick me. The more the audience lose their discipline the more they find their inner Toby Belches. And the more they find their inner Toby Belches the more I can be Malvolio in opposition to them. There’s a moment in the show when I leave the audience to themselves – like a teacher leaving the classroom. It is my hope that in this moment the audience will stage a minor coup. This has happened to greater and lesser degrees in the life of the show. In China, recently, one audience member destroyed a rather key prop while I was off stage. This was a little more that I had anticipated, but the audience were all in on the individual’s act and it led to some strong interactions around corporate blame and responsibility… My job is to deal with whatever is thrown at me. In that sense, the show is a bit like a stand-up act. It treads the same knife-edge.

I am only ever truly wrong-footed by an audience who sits in respectful silence throughout. My main task in the performance is to make sure this doesn’t happen. I talk about setting a fire under the audience, not to kill them, but to thaw them out and bring them to life – with all the contingent consequences.

Where did the idea of commercialising an unceasing tide of audience abuse first find its appeal with you, because this isn’t the first time you’ve used it in a show, is it?

That question is questionable on so many levels! Lots of assumptions about commercialisation, abuse, my work and tides – a tide can’t be unceasing, it comes in and then it goes out – that’s what makes it a tide.

My work is born out of respect for an audience. The height of audience abuse is, in my opinion, to ignore them altogether – and my work NEVER does this. It never puts them in the dark and dazzles them with spectacle – that is the domain of truly commercial theatre, a theatre that focusses on replicability and numbers, on quantity not quality. My work calls upon an audience to think alongside the performer and the writer, to be seen, to be present – and to have their presence acknowledged. No two performances of my work are the same – and this is deeply un-commercial…

I admit that my Malvolio doesn’t like his audience. Or, rather, he hates all audiences. He hates theatre. He hates art and culture. So in one respect, your accusation of audience abuse is correct. A reviewer once described I, Malvolio as a sustained ‘reverse heckle’ – and this feels right. The audience are never let off the hook in I, Malvolio. Their practices are interrogated throughout the show but, most importantly, they are acknowledged and, in a roundabout way, encouraged. The audience becomes the subject of the performance. This feels like respect, not abuse.

When you write and present Shakespeare for a TEENAGE audience, what are the differences between that and writing for ‘proper grown-ups’?

Show me a ‘proper grown-up’. I don’t know what they look like. I don’t believe they exist.

Writing for theatre is about giving form to an idea – through narrative, structure, staging, etc. It’s about materialising thought in space and bringing the presence of an audience to bear on that thought – to change it, challenge it, to make it their own. This applies to working with Shakespeare as it does to anything. The rules are the same. I’m excited by the ideas and forms in Shakespeare’s plays. Shakespeare and I share some thoughts about simple staging, about trusting the audience’s imagination and intelligence, about language (he’s a lot better at it than me). I try to stay true to these precepts in everything I write – for young or adult audiences.

Writing for young people requires you to think about your audience – and that’s a good thing. Every writer needs to think about their audience when they write. Young people are usually much more accepting of invention. They don’t come to the theatre with a whole set of preconceptions. They are open to what you bring. Also, it’s impossible to lie to a young audience – they can sniff out fakes very easily. I love the immediacy of their response – they understand the idea of ‘play’ within a play.

But these are all rules I’d apply to writing for an adult audience as well.

When I, Malvolio opened back in 2010, the Brighton festival asked me to do a ‘late night’ version in addition to the family one. I thought about this, talked about this – and then came to the conclusion that I should do the same thing for both. In the late night version my ad-libbing took a more adult approach – but the play itself works for all ages. It responds to the people in the room. If those people are slightly drunk grown-ups – then I play the show to them. Different every time dependent on who’s with me.

Aside from being offended (!) what is it you hope audience members leave with after spending their evening with Malvolio?

What kind of a sadist do you take me for?

[pull_left] I, Malvolio is not offensive. It does ask the audience to consider why the hell they’ve come to the theatre; and what their responsibilities are once they’re there[/pull_left]

It’s never my hope to offend an audience. I suppose you could say that it’s my hope to activate an audience, to stir an audience, to gently provoke an audience – but never offend. (Also, it’s my primary aim above all to entertain an audience.) I, Malvolio is not offensive. It does ask the audience to consider why the hell they’ve come to the theatre; and what their responsibilities are once they’re there. The play is about cruelty, about the pleasure we get from watching people being cruel to others (how we laugh when Toby Belch destroys Malvolio with a vicious practical joke). I work this idea to quite an extreme level – particularly for a young audience – but this is theatre’s strength. To go to a difficult place but to go there safely. I think any audience that sees I, Malvolio knows what’s going on – they know that a game is being played. A serious game at times, but a fun one. Through games, as through plays, we practise our behaviour – and I, Malvolio does just this. (In Twelfth Night Maria describes Malvolio as being ‘in the sun practising behaviour to his own shadow’. This feels right.)

A one-man show like this is tremendously demanding, have you ever forgotten where you are completely during a show?

[pull_left]We love it when an actor f**ks up – no matter how much they suffer for it. I, Malvolio trades in these moments[/pull_left]Yes. Regularly. And I suppose I must say that these are the best moments – in terms of the nature of the show. In performance, I’m operating on many levels. My brain is not only thinking about the text and the present moment; it is also thinking ahead in time and space – about the audience, about its responses, its involvement. Sometimes my brain starts to hurt with the effort. And sometimes it fails me completely. I don’t try to cover those moments up. I encourage the audience to laugh at my failure and then attack them for their cruelty – their enjoyment in watching an actor drowning on stage. It’s a pleasurable thing, isn’t it? We love it when an actor fucks up – no matter how much they suffer for it. I, Malvolio trades in these moments – moments of disaster and the loss of control. My work is striving for those things because it’s what makes theatre live. I brought a show to Melbourne in 2009 called An Oak Tree – a show which has a different second actor in it every time it’s played. An actor who has neither seen nor read the play they’re in until they’re in it. This means that every time I perform that play with a new actor it is a different experience. And every time it fucks up. The fuck ups are the best thing. They prove that, in art, nothing should be perfect.

What do you think is so powerful about Shakespeare, and how can you account for the success that I, Malvolio has already enjoyed?

You don’t need to know Twelfth Night to get I, Malvolio. My play stands alone as a roar of existential angst against an audience. The fact that it references Shakespeare, however, deepens its appeal. It connects it to a historical sensibility and a sense of how these characters are timeless. Nothing I do as Malvolio in my show would not feasibly have been done by Malvolio in Shakespeare’s play – even down to the leopard print g-string… I slip in and out of Shakespeare; I tell the story of Twelfth Night. But this is also a contemporary piece of theatre that explores ideas I am engaged with in all my work. I am not treading water to make work for young people. If anything, I move forwards further with these solo Shakespeare pieces.

I, Malvoio is the fourth in a series of five plays that take a minor character from Shakespeare and let them run free. It’s been the most successful of them perhaps because it is the most dialogic. The audience are cast as a character – a character they’re well versed in playing. This is not a one man show – it involves us all.

What is Malvolio’s sexual fantasy, and on an unrelated note, how did Malvolio spend his Christmas this year?

Shakespeare has already written it:

“…(sitting) in my branched velvet gown; having come from a day-bed, where I have left Olivia sleeping…”

His fantasy life is strong! In Twelfth Night he makes a fool of himself for love. He dresses absurdly, he smiles like a idiot, he behaves like an ass. I imagine all his sexual fantasies exist around this kind of role play, otherwise his gulling wouldn’t have been so successful. Somewhere in the fantasy would also be the abject domination of Toby Belch – a gimp mask, whips, straps, strap-on, etc….

Christmas for the poor man would have been spent seething in fury at the commercialisation of the birth of Christ. Sitting with some dried biscuits and a glass of water, nursing an ulcer, reading the bible.

I hate him and I love him.

I, Malvolio will play at the Arts Centre, Melbourne from the 6 January 2015.

Tickets available from $30. Show is 60 minutes with no intermission.

Visit Arts Centre Melbourne for all booking enquiries.

For more information on Tim Crouch, check out his official website