A squeaky clean chat with Cry Baby’s Alexander Berlage

John Waters’ film Cry Baby has long been a cult-favourite, but it wasn’t until 2007 that it hit the world of musical theatre.

Cult fanbases often grow as a response to the mainstream rejection of a piece of text – this can be because of a poorly written script or book, or simply because it stood against the societal norms of its time of conception. The Rocky Horror Show and Little Shop of Horrors are seen as some of the most influential and recognisable cult musicals, however there are many others that flit through the theatre world. Of late, many cult films have been adapted into full-length musicals to capitalise on their success (Lawrence O’Keefe’s Heathers is a prime example).

John Waters, the self-proclaimed “king of trash,” is notorious for his lewd and crazy filmmaking. A previous adaptation of one of his most famous films, Hairspray, took a much more family-friendly position on the stage – this is not the case for Cry Baby. Although sharing the same local Baltimorean setting, Cry Baby is a camp-tactic mash of teen angst and violence, with some anti-polio vaxxers thrown in for good measure. Hayes Theatre Co. are following their string of successful cult-musical seasons with Cry Baby, bringing it to the stage under the directorial vision of Alexander Berlage.

I had the opportunity to speak to Alex ahead of the show’s opening to discuss the crazy 2 hours of insanity that is Cry Baby… and just why we love it.

So… why Cry Baby?

This is actually the first musical that I’ve directed. I’ve lit a few shows at the Hayes before, but I’m so excited to have this opportunity. In terms of selecting a project, when it comes to picking musicals that I’m wanting in working on I’ve never been the person to want to do Wicked or Legally Blonde, I much prefer the smaller, more quirky show. I’m more interested in what’s possible for the show to say, and where it sits here, now, in our current society. I think Cry Baby is such an interesting piece because it’s so outrageous and so camp, yet it says quite pertinent things about class, an inherent bigotry, and fear of the other. In a time where there’s been such great social movements in finding equality and a more diverse acceptance of race, class, gender and sexuality, I think it just furthers that conversation and looks at where we were as a people and how far we have (or in some respects, haven’t) come. And if an opportunity to direct a show based on a John Waters film at the Hayes theatre comes up, who is going to say no to that?

How has directing the show been for you?

It’s been quite daunting because there are so many moments where we just think what John Waters would do, and if we are doing that justice. Are we being too safe? Are we going too far? It’s so hard to know where you draw the line. He made the film in the early 90s, and the show came out in 2007-2008, so there’s been almost 30 years since the film came out and now over 10 since the show came out – the world has changed so much since then. Finding the balance of making it understandable now while still keeping it relatable to the current time has been a really interesting journey. We want to preserve that fun flavour and camp-ness but still ruffle a few feathers.

Why is it that you think cult musicals are still widely successful and are continuing in production?

I think when you look at all the cult movies that have been turned into musicals, the big thing that links them all is this sort of battle between the ‘norm’ and the ‘other’ – if you look at Mean Girls, Zombie Prom, Carrie, Rocky Horror, it’s basically this group of others that are shaking up and causing tension with the norm. I think this is really what underpins the general sort of vibe of all great cult movies and musicals. The reason they work is that when you look at the general audiences that love musicals, we’re all theatre kids. We all have an experience of being the ‘other’ at some point in our life, whether it be because of class, gender, or something else. We can relate with that feeling of not fitting in and trying to just be who we are, fighting against the status quo. There’s something that makes them feel like home, this familiarity in the celebration of individuality. You can be who you are – it’s kooky, it’s cool, it’s beautiful and amazing.

John Waters has a very distinct aesthetic and thematic style in his films – are you going to try and reference these in your production?

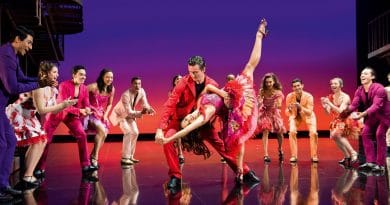

The film was a 1990s version of the 1950s, so we’re creating a 2018 version of the 1950s, and how that time looks from where we are now. Aesthetically we’ve having lots of fun with the colour palettes, the Squares are all pastel and the Drapes are big and bold, and we’re playing with lots of different textures as well. We also want to find little ways to subvert things to make them seem as more relevant to today. In the film there’s a big focus on cars and obviously at the [Hayes] theatre we can’t exactly have them driving in because of the space, so we have to look at how we can adapt that to fit our stage and focus on the people and humans rather than the objects and things they inhabited. The film itself moves around location wise so much so the first thing the set designer (Isabel Hudson) and I discussed is that we aren’t interested in being specific but rather think about what we are trying to evoke or what the theme is, resulting in a space that is a pretty universal reflection of what the 1950s felt like. John Waters’ films had such a heightened sense of reality and were so out there and theatrical, they lend themselves so well to being staged. I don’t think there’s ever been this much colour in the Hayes.

How do you think Cry Baby is different from other musicals?

When I first listened to the soundtrack I thought it sounded fun and like every other rock n’ roll sort of musical. But the more you listen to it and what they’re saying, you realise just how smart it all is. The music is very sanitised and fun, but the lyrics… There’s a song called “Can I Kiss You With Tongue?” which is basically an ode to consent, or “The Anti Polio Picnic” where they’re talking about how fun their lives are and doing a dance routine around a person with polio and an iron lung. It’s so outrageous and quite provocative.

What is your main goal with this production?

Our big thing is to shake things up. It’s been such an amazing program in the last few years [at Hayes] but this is going to be pretty wild. It might shake the locals up a bit, who knows! I’m not making a nice night at the theatre for people to clap along. At the end of the day, we are artists and we make work to say something, and hopefully shift perspectives. if we’re not actively making audiences have a think, we’re not actually making art, but are just making decorations. In Hairspray he slipped in so many subtle things and it was amazing that these made it to the mainstream – a white girl falling in love with an African American man, two men singing a romantic duet to each other (albeit one in drag). Cry Baby does that but… to a much more extreme and much less subtle way. It’s so exciting to direct this show in a theatre which has such an amazing reputation and to try and push the envelope a bit more on certain ideas of race, class and sexuality.

Cry Baby opens at the Hayes Theatre Co., Potts Point, from July 20th. Tickets are on sale at the Hayes Theatre Co. website.