Politics and Theatre: A Love/Hate Relationship

Almost since humans started living in social groupings theatre has been a part of life. The period often cited as the birth of theatre is some 6000 years ago in ancient Mesopotamia. As with many ancient cultures, the balance between theatre and religious or ritualistic ceremony is a bit touch of a grey line, and thus questionable as to whether it could indeed be called theatre.

No one would dispute that ancient Greece had real theatre in abundance. Often separated from religion, it is very clearly theatre with drama, actors, stages and paying audiences hence why many see ancient Greece actually as the birth of theatre.

The movement from religious or ceremonial theatre, to what we think of as theatre today was often accompanied by a wish to get across a particular message; be it moral or political or address current events. Greek plays did just that and exercised considerable influence on public opinion. Performances took place in amphitheatres, the same central arenas that were used for religious ceremonies and political gatherings. In Athens, the power was in the hands of the citizens, who gathered to make decisions on the law, on domestic and foreign policy, and war and alliance related concerns. Theatre taking place in the same venue was thus a natural part of the debate.

Scholars mostly agree that it was in Greek theatre that the refinement of the democratic system took place. Is it a coincidence that theatre as we know it was created in classical Athens, which is also the birthplace of democracy? Most of the plays by Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides or Aristophanes were composed and performed under the emergence of democracy. The relationship between theatre and politics was that of sister and brother.

Greek democracy, created in Athens, was direct, rather than representative, which meant that any adult male citizen over the age of 20 had a duty to take part. The officials of the democracy were in part elected by the Assembly and in large part chosen by lottery. Theatre was a way of educating them to make wise and considered decisions. There are several plays where the characters bring on the disaster through bad decision making, without listening to good counsellors.

Greek theatre thus caused reflection and thinking, dialogue and debate. It was an essential element for the self-awareness of the community, not just entertainment. Taking topics of primary importance as well as more immediate issues, the theatre was, therefore, a natural complement to the Assembly.

HE WHO PAYS THE BILL

In the right context, therefore, theatre is a powerful tool for social change. Examples can be found in all periods of history and many cultures. But how free is the playwright from the political establishment under which they write? If you don’t keep the patron happy you might find your funding gone, or even worse, your head.

The Habsburg dynasty ruled Austria and a vast tract of central Europe for several centuries in the middle ages. Their influence throughout Europe was far-reaching. Their patronage of the arts was extremely influential, and the nobility followed their royal leaders lead. Without their involvement, the arts would have developed very differently in Europe.

Their influence might have been far-reaching geographically at the time, but their presence is still felt today. In 1498, Emperor Maximilian gave the instructions to add boys to the choir of the court chapel, seeding the world-famous Vienna Boys Choir, still in existence today.

A royal wedding in 1622 strengthening Austria’s link to Italy and all things Italian. The new Italian Empresses’ coronation was celebrated with the first-ever large-scale ballet performance in Vienna. She went on to introduce Italian opera, which was still a fledgeling musical art form, to Austria. Artists began to earn serious money, and look for royal, or at least noble patronage.

One Emperor, Leopold even composed his own music and spent a large fortune on his Court musicians on commissioning a new theatre. He hired Italian theatre engineers to design and build elaborate props and sets for the performances.

Emperor, Charles VI, was also a composer and both his daughters, Maria Anna and Maria Theresa, sang and performed in court for the entertainment of the imperial couple and an exclusive audience. It was in the same Maria Theresa’s Court that six-year-old Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart performed on the piano. One of the royal sons even studied piano and composition with Beethoven in 1804.

The story goes that Beethoven received an offer from Jerome Bonaparte, the famous Napoleon’s brother, to his court. Beethoven initially accepted the offer, but upon hearing this, Archduke Rudolph of Austria persuaded two other nobles, to pool their resources with his and pay Beethoven an annual pension as long as he stayed in Vienna.

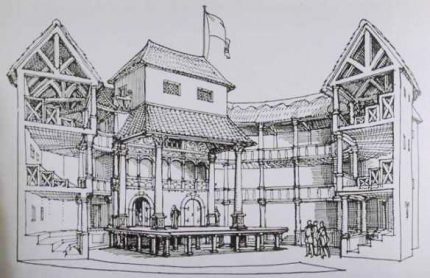

Meanwhile something major was happening on an island outside of the Hapsburg area of influence: Great Britain. During the period ending the Tudor dynasty with Queen Elizabeth, I of England and the beginning of the Stuart dynasty with James I theatre took on a whole different dimension.

Until the late 16th-century theatre in England tended to take place in outdoor marketplaces or churches and be strongly influenced by the church. The church using performances to convert people to Christianity but slowly, royalty became the patrons.

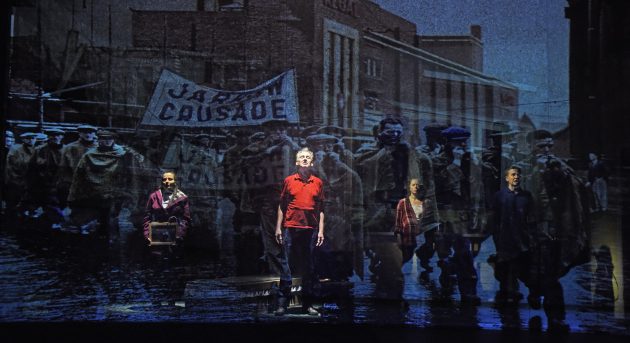

Real issues of contemporary culture were played out on stage for the general public. The public was a mixture of people from all classes, races, and genders. It gave them a place to think about society. Instead of religious and morality plays, writers brought politics, race, and class issues to the stage for the first time in the UK.

But theatre in buildings meant financing seriously entered the equation and the authorities wary, and they often looked for ways to control or close theatres. People in high places try to control what was performed. From Queen Elizabeth I to her rich and influential courtiers.

Shortly after he arrived in London, King James I insisted that Shakespeare’s troupe come under his patronage and change their name to The Kings Men. This patronage provided opportunities and made Shakespeare a wealthy man, but there was a price to pay. Macbeth, set in James homeland Scotland, is a good example of a play full of flattery to a king who held the purse strings — even taking liberties with history to flatter the King’s ancestors.

Shakespeare was, therefore, given that artists difficult choice: To be or not to be bowing to the patron, that is the question? Many of his plays disguise themes to maintain royal patronage. Nevertheless, He made many political statements in his plays, sometimes hidden, sometimes quite blatant. Many plays brought to discuss some of the important political issues of the time, especially the direct way he examines how power works at the highest levels. Some plays explore the machinations of personal ambitions and passions of royal leaders and how that determined the politics of the country. Two of the strongest examples of this are Macbeth and King Lear, which dramatize political leadership and complexity subterfuges of human beings driven by the lust for power.

IMPOSSIBLE TO SURPRESS

Many a dictator has suppressed art he didn’t have full control over, didn’t like, or felt might work detrimental to his vision, from Hitler to Chairman Mao. Yet often the arts found their way in one form or another, a little like land wasted by a fire, will grow back new green shoots. Perhaps the theatre becomes influenced and stronger by the resistance. Would Catalonian traditional dance and songs still exist so strongly today if first Franco and then the central government of Madrid didn’t suppress or challenge their culture?

Portuguese Fado is said to be the saddest music in the world. A mix of Portuguese and Brazilian immigrants in the working-class areas of Lisbon fado is a social and political commentary. It moved from the restricted underground pubs and brothel to appear on stage for the first time in 1869, in the comedy “Ditoso Fado” and went on to become a major musical genre in Portuguese theatre.

After a coup d’état installed a fascist dictatorship in 1926 Fado was seen as subversive as it had been mostly a left-wing, working-class, socialist-oriented type of song. In 1927, laws were introduced subjecting all lyrics to censorship. Songs that had not been approved were not allowed to be sung in public. In 1936 the regime ran a series of radio broadcasts entitled Fado, the Song of the Defeated, in effect consigning the genre to history. But Fado continued to be sung behind closed doors, refusing to be suppressed.

Theatre has thus long been used to express opinions and garner public opinion, to give food for thought and educate. It is intrinsically wound into our society, from the productions that we watch onstage, to the theatrical techniques used by the politicians that run our country. In the Western world’s modern democracies, the theatre has lost the dual relationship it had in ancient Greece. Although there are many politically themed plays around, some politicians never attend the theatre, and thus totally miss any messages that might be directed at them.

Shakespeare lived his entire life in the shadow of the bubonic plague. A few months after his birth, the epidemic took the lives some fifth of the population of Stratford, the town where he was born.

With the help of strict quarantines and the plague was brought to a standstill only to return some years later only to repeat the process when that epidemic was brought under control.

The plagues could be said to plague Shakespeare’s life with some economically devastating lockdowns. Luckily Shakespeare was not discouraged from producing plays. According to one theatre historian, the years between 1606 and 1610, when Shakespeare wrote and produced some of his greatest plays; Macbeth, Antony and Cleopatra, The Winter’s Tale and The Tempest, the London theatres were not likely to have been open for more than a total of nine months. Yet like the plants after the fire, over the centuries the plays grew from strength to strength. Nothing can extinguish the light of good theatre.